Primary Healthcare Push Gains Momentum

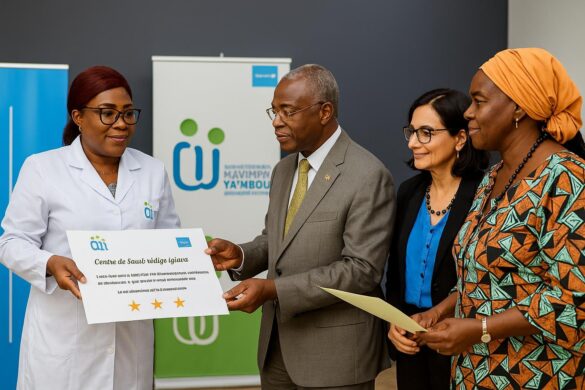

Nineteen integrated health centers in Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire have passed the final stage to obtain quality certification, the Ministry of Health officially announced in late November.

This milestone culminates eighteen months of work under Mavimpi Ya Mbote, a UNICEF-supported model that places mothers and newborns at the center of care.

Officials describe this achievement as a decisive shift toward equitable primary healthcare services, echoing the declarations of Alma-Ata in 1978 and Astana in 2018 on universal coverage goals.

Certification depended on meeting thirty performance indicators, ranging from the presence of skilled birth attendants to cold chain management, assessed by joint teams from the districts, UNICEF, and the ministry.

How the Mavimpi Ya Mbote Model Works

Mavimpi Ya Mbote roughly translates to “Dream of Good Health” in Kituba, expressing the ambition to make respectful, life-saving care the daily standard nationwide.

This approach integrates clinical protocols, community mobilization, and on-site coaching, replacing sporadic supervisory missions with weekly mentorship within each facility by senior nurses.

Caregivers track labor stages on simplified partographs, weigh newborns within the first hour, and counsel mothers on exclusive breastfeeding, using visible scorecards for visiting families.

Data is integrated into the district health information software, allowing managers to identify stock or skill gaps and intervene before complications worsen.

Impact of Certification in Two Major Cities

The average quality of services in ten pilot districts rose from 48.9% to 76.6% over eighteen months, according to ministry scorecards validated by UNICEF.

Facilities that crossed the threshold now display a green emblem near their entrance, signaling that obstetric emergencies and childhood illnesses meet proven standards.

At CSi Mboukou Bernard in Mvou-Mvou, Pointe-Noire, deliveries increased by 30% after certification, a midwife noted, attributing this to restored trust from mothers and fathers.

Urban clinics were not the only beneficiaries; rural outposts like Nganga-Lingolo reported reduced referral times to hospitals because complications are detected earlier and managed.

Testimonies from Clinics and Communities

The UNICEF Representative told journalists she was “impressed by the commitment and skill” observed during her visit to certified sites in Congo in November.

Philomène, a 27-year-old mother in the Tié-Tié district, recounted that nurses no longer ask families to buy gloves for delivery, a change she says saved her baby.

A community health worker said he now receives digital alerts from clinics when a newborn misses vaccines, enabling door-to-door follow-up within two days.

A Red Cross branch reported fewer malaria complications in children under five, attributing part of the decline to stricter triage and prompt treatment at certified points.

Scaling Up to Meet SDG 3 Targets

Bolstered by the results, the ministry has instructed provincial directors to integrate Mavimpi Ya Mbote into annual work plans for 2024, seeking cabinet approval next quarter.

Officials state that a national rollout would accelerate progress toward Sustainable Development Goal 3, whose targets include reducing neonatal mortality to twelve per thousand live births.

Congolese neonatal mortality was near 22 per thousand in 2022, according to WHO estimates, highlighting the urgency of consistent primary care everywhere.

Partners have informally signaled interest, but detailed funding commitments will depend on an upcoming investment study.

Funding, Training, and Digital Tools

Initial implementation relied on pooled funds, as well as national resources channeled through performance-based budgets at district and facility levels.

Each certified center now receives a modest premium reserved for staff incentives, emergency drugs, and minor repairs, subject to quarterly verification by external assessors.

Nurses underwent four training modules covering neonatal resuscitation, respectful maternity care, waste management, and data audit, delivered by national tutors themselves trained abroad.

A mobile dashboard aggregates key indicators, turning red when antenatal care attendance falls below 80%, prompting supervisors to dispatch awareness caravans within two days.

Regional Interest Within the CEMAC Bloc

Health delegations from Cameroon and Gabon visited Brazzaville in October to observe Mavimpi Ya Mbote sessions, exploring possibilities for cross-border learning under CEMAC structures.

The Economic and Monetary Community already pools vaccine purchases and could, analysts say, extend common quality assurance tools to maternal health across member states.

Such collaboration could cut consultancy costs and speed up certification timelines, a advisor suggested at the recent Central African Health Ministers’ forum.

However, observers warn that languages, data systems, and funding cycles differ, requiring adaptation rather than a copy-paste adoption of the Congolese model in each country.

Next Steps for Congolese Maternal Care

For now, health authorities plan follow-up audits every six months to maintain the green emblem’s meaning and prevent complacency over time.

New construction guidelines will integrate Mavimpi Ya Mbote standards into design, from ventilation to handwashing stations, so future facilities start above the baseline curve.

Academic partners will assess patient satisfaction and cost-effectiveness, providing evidence for a policy brief expected mid-2024, intended for cabinet health committee review.

If approved, the model could reshape frontline care across Congo-Brazzaville, positioning the country as a regional example of pragmatic quality improvement in primary health.